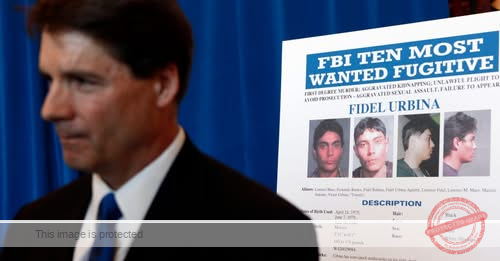

For more than 17 years, one of the FBI’s “Most Wanted” fugitives was hiding out in Mexico.

Charged in 1998 with the rape and murder of a 22-year-old woman in Back of the Yards, Fidel Urbina evaded capture until 2016, when he was arrested by Mexican federal authorities on a U.S. extradition warrant.

He has remained in Cook County Jail ever since, awaiting trial in the alleged murder of Gabriella Torres — a case that originated during the Clinton administration.

There could be an end to the saga within sight. In recent weeks, a Cook County judge finally set aside time in November to hear Urbina’s jury trial, while a motion to suppress evidence gathered at the crime scene was also denied.

But another crucial pretrial ruling is still to come — stemming from a 53-year-old Chicago police misconduct investigation into the lead detective in the murder case — leaving the door open to more potential delays.

Earlier this year, prosecutors made a disclosure to the court and Urbina’s attorneys. A key witness, the since-retired Chicago Police Department detective who investigated Torres’ killing, informed the state’s attorney’s office that he was suspended for a month without pay in 1972 after he was accused of stealing cash from a civilian’s wallet.

The detective, who retired from CPD in 2009, denied any wrongdoing and said he underwent a polygraph examination, prosecutors wrote. The Police Department had no records of the suspension or internal investigation on file.

Prosecutors met with the retired detective in March 2023 to discuss the case. It was then, prosecutors said, that he informed them of the suspension.

“In approximately 1972, (the detective) was accused of taking money from an accident victim’s wallet while on duty,” prosecutors said in a notice of disclosure. “(The detective) submitted to a polygraph examination and was subject to a 30 day suspension without pay. (The detective) denied any wrongdoing. After learning this information, (prosecutors) requested additional information from the Chicago Police Department and were informed there are no records on this matter.”

A state’s attorney’s office spokesperson declined to comment on the still pending case. In their motion, though, prosecutors said questions about the suspension would amount to a highly prejudicial fishing expedition unrelated to the charges Urbina faces.

But what seems like a minor infraction many years ago could be a stumbling block. In a statement, the Cook County public defender’s office said the failure to maintain those disciplinary records “undermines fairness in the criminal court system.”

“Earlier this year, our attorneys learned of a former detective’s suspension for misconduct, yet the department could not produce the underlying records,” a spokesperson for the office said in a statement. “The failure to keep these records long term hinders the ability of the courts to fully assess officers’ credibility, which is particularly concerning given our county’s long history of wrongful convictions tied to police misconduct.”

Prosecutors and Urbina’s defense are expected to argue the motion during Urbina’s next hearing in the winding case this month.

A horrific attack

On Oct. 21, 1998, Urbina was working in an auto shop when 22-year-old Gabriella Torres took her car in to get the brakes fixed. Authorities allege that Urbina raped, beat and strangled her inside the shop before binding her body and stuffing it into the trunk of a stolen 1990 Chevrolet Lumina.

At the time, Urbina was out on bond while he faced charges in another pending sexual assault case that originated earlier that year.

According to police, Urbina enlisted the help of two men to push the car into a nearby alley, where he doused the vehicle with gasoline and lit it on fire. The two men were seen running from the burning vehicle and were later arrested and charged with arson, although there was no evidence they were aware that Torres’ body was in the trunk.

Five days later, Urbina failed to appear for a court date in the rape case and a warrant was issued for his arrest, records show.

The two men charged with arson in connection with the killing both pleaded guilty and were sentenced to three and six years in prison, respectively, according to county court records.

But Urbina was nowhere to be found.

Less than a year after Torres’ death, a federal arrest warrant was issued for Urbina. In 2006, a Mexican federal magistrate judge signed another provisional arrest warrant.

In 2012, the FBI added him to its Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Four years later, he was found hiding in a small town in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Eventually, he was extradited back to Chicago.

“Fidel Urbina was wanted for his alleged role in two brutal attacks directed against innocent women,” Michael Anderson, then the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Chicago field office, said in 2016 after Urbina’s arrest. “Many family members have waited a long time for this day to come and they deserve the opportunity to face the accused in a court of law.”

While he’s been in Cook County Jail on a murder charge, court records show Urbina’s other case — another sexual assault charge that also originated in 1998 — was adjudicated last year.

In April 2024, Urbina pleaded guilty to one count of criminal sexual assault and was sentenced to six years in prison, records show.

Torres’ family and the retired detective could not be reached for comment.

Key rule violation

The misconduct by the retired detective — theft and lying during a polygraph — could, in theory, amount to a violation of CPD’s Rule 14, which forbids officers from “making a false report, written or oral.”

CPD officers with sustained Rule 14 violations are effectively barred from any future police work that would require them to testify in court, as they’d be subject to cross-examination by defense attorneys.

Brazen, often criminal misconduct by CPD officers was far more common in the 1970s, when the department’s internal oversight mechanisms were still relatively new.

In decades past, the city’s collective bargaining agreements with the Fraternal Order of Police allowed for the destruction of disciplinary records more than 5 years old. Ultimately, in 2020, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that contract provision went against well-established public policy.

That year, and again in 2021, the city’s Office of Inspector General probed CPD’s recordkeeping and production practices. OIG found the Police Department was “unable to ensure that it can meet legal and constitutional obligations which are at the core of its function as a law enforcement agency.

“This is an area of very serious risk for CPD and for the City,” OIG concluded. “In criminal litigation, CPD’s failure to identify and produce records and information in its possession might undermine criminal prosecutions or lead to vacated convictions. In civil litigation, the same failures may result in significant legal and financial liability.”

Uncertain path forward

Even in Cook County, a criminal court system known to struggle with delays, the Urbina case stands out for the sheer age of the crime.

Last month, the judge overseeing the case denied a motion to suppress much of the prosecution’s evidence, which collected inside a garage near the 1998 crime scene. The next hearing in the case is scheduled for later this month, records show.

Craig Futterman, a University of Chicago law professor who directs the law school’s Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project, stressed that, “in cases where someone’s defense rests in part on the honesty or dishonesty of the testimony of a police officer or a detective, or rests on alleged misconduct by that police officer or detective, the absence of bad evidence would be an out-and-out denial or could be an out-and-out denial of due process.”

The full effect of the officer’s alleged conduct, and the apparent delay in the Urbina defense knowing about it, remains to be seen.

“What’s head-scratching to me is that (the alleged misconduct) occurring in 1972, that’s not something that you just get a suspension over,” Futterman said. “If you’re caught stealing, that’s the end of your police career.”

“There’s another underlying policy issue of a police officer who was found guilty of stealing — and stealing on the job — is then allowed to continue to have a badge and a gun. … It’s unconscionable.”